Heritage Art/Getty Images

Fueled by the Supreme Court’s June 2023 ruling that bans affirmative action in higher education, conservative lawmakers across the country have advanced their own state bans on diversity initiatives, especially those that might make students feel shame or guilt for past harms against people of color.

This effort encompasses medical schools.

Despite clear and persistent gaps between white and Black doctors – and recent efforts to reckon with racial disparities within the medical profession – lawmakers have tried to advance policies to prohibit diversity initiatives in medicine.

North Carolina Congressman Greg Murphy introduced one such bill to restrict diversity initiatives. “American medical schools are no place for discrimination,” said Murphy, a Republican, in March 2024. “Diversity strengthens medicine, but not if it’s achieved through exclusionary practices … of prejudice and divisive ideology.”

But the gaps in racial representation in medicine go beyond a professional numbers game. Modern research shows that the lack of Black doctors helps explain why about 70% of Black people don’t trust their doctors, and why Black people tend to die younger than their white peers.

The evidence is clear: America needs more Black doctors.

According to a 2022 survey of 950,000 doctors by the Association of American Medical Colleges, 63.9% reported their ethnicity as white, and just 5.7% Black or African American. But according to 2023 estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, Black people comprised 13.6% of the population, while white people represent 58.9%.

These modern inequalities in medicine have deep roots. As a community health professor, I am always curious how today’s racial health disparities formed in the first place. One window into this history is through the official physician directories published by the American Medical Association, or AMA.

A limited landscape

Starting in 1906, the AMA has published directories of all qualified physicians in the U.S. These directories were created to be comprehensive records that excluded “quack” physicians and unqualified graduates of fraudulent medical schools.

Each physician’s record included a variety of details, including their place of practice and when and where they completed medical training.

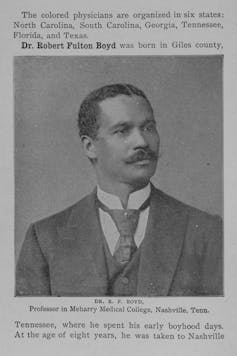

Between 1906 and 1940, the AMA also insisted on publishing the race of Black doctors. Beside each entry appeared the label “col.” for “colored.”

Based on this information, I created a digitized dataset of the 1906 directory and detailed geographic and demographic patterns associated with where Black doctors trained and practiced. Of the 41,828 physicians listed in the 1906 directory, only 746 were Black – or 1.8%.

Heritage Art/ Getty Images

Most Black doctors in the South were trained by a handful of Southern medical schools established to educate African Americans. Over half – 57% – of Southern Black physicians attended Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, or Howard University Medical School in Washington, D.C. – schools that are still in existence.

But nearly a third – 29% – of Southern Black physicians attended schools that would be closed a few years after the 1906 directory’s release. In 1910, at the behest of the AMA, educator Abraham Flexner released a report after studying the standards of medical schools in the U.S. and Canada.

The results of the Flexner report was devastating to the number of Black doctors. Citing low admissions standards and poor quality of education, Flexner recommended closing five of the seven historically Black medical schools that trained the vast majority of Black doctors.

By 1912, three Black medical schools were shut down. By 1924, only two remained in operation – Meharry and Howard.

The consequences of this extremely limited educational landscape for aspiring Black physicians are reflected in the data. In most Southern states, the distance between medical school and practice locations was significantly greater, even before the closings, for Black doctors compared with their white counterparts.

The deep roots of inequalities

To help interpret where Black doctors established practices in the South, I also linked directory data to other historical sources, including the U.S. Census.

What I found was that places with larger Black populations were more likely to have a Black doctor, as were places that were closer to a Black medical school.

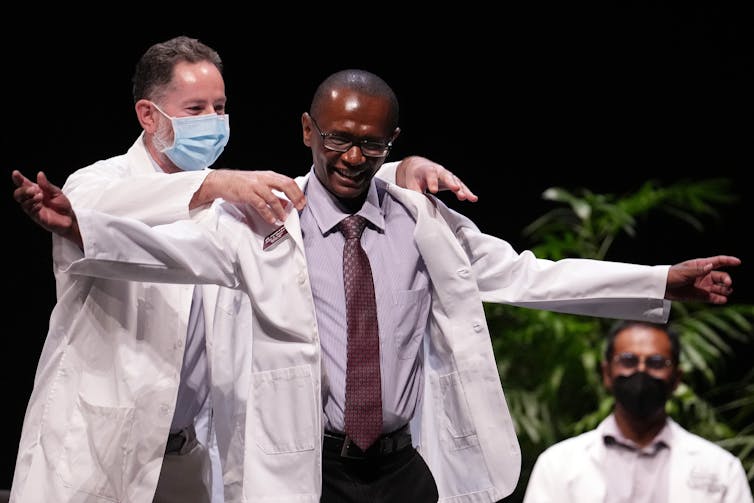

Anthony Souffle/Star Tribune via Getty Images

Many contemporary scholars and activists are looking to the past in order to increase the public’s understanding of how race has played a historical role in the health outcomes of Black Americans.

For example, Dr. Uché Blackstock, a Black physician, illustrates many instances of medical racism throughout American history in her most recent book, “Legacy: A Black Physician Reckons with Racism in Medicine,” and shows their lasting impacts on how Black patients are treated and the quality of health care they receive.

She was one of the first, for example, to warn health officials about the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color. As she wrote in 2020: Black Americans were more vulnerable during the pandemic “because of several manifestations of structural racism, including lack of access to testing, a higher chronic disease burden and racial bias within health care institutions.”

Without an accounting of how racial disparities in medicine were formed, it’s much more difficult to determine which kinds of progressive measures are needed to provide redress.

Future analyses will help unpack these racial disparities in greater detail. But for now, both academic researchers and the public can use our data to explore the importance of historically Black medical schools and the lives of Black physicians during the Jim Crow era.

It’s my belief that their legacies deserve to be a better-known part of the history of American medicine.![]()

Benjamin Chrisinger, Assistant Professor, Community Health, Tufts University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()